(3rd September 1939 – 8th May 1945)

The Battle of the Atlantic was the longest Battle of the entire war. It started the day that Neville Chamberlain declared war on Germany. It ended on the day that Germany surrendered five-and-a-half years later.

The Battle accounted for (on all sides) over 100,000 casualties and the loss of over 3,500 merchant ships and over 1,000 warships (including U-Boats).The conflict in the Atlantic Ocean is perceived as bringing Britain to the point of starvation and nearly leaving the country without the necessary resources to continue fighting the war.

About the Battle Churchill said, “The ‘U-boat peril’ was the only thing that ever really frightened me.”

“The ‘U-boat peril’ was the only thing that ever really frightened me.”

– Winston Churchill

On the 5th March, 1941, the First Lord of the Admiralty, A. V. Alexander asked Parliament for, “Many more ships and great numbers of men to fight the Battle of the Atlantic”. Within a fortnight the government had established their Battle of the Atlantic Committee.

It was at this moment that all the diverse skirmishes, conflicts and attacks upon shipping in the Atlantic were brought together by the British under one name and one strategy, the Battle of the Atlantic. Henceforth, the entire conflict in the Atlantic Ocean during the Second World War became known by this name.

It was the longest, largest, and most complex naval battle in history. It was a continuous military campaign that started on the 3rd September 1939 and only finally ended when Nazi Germany surrendered on 7th May 1945 – five years, eight months and four days (or 2,073 days) later.

More ships and more sailors were lost in the Battle of the Atlantic than any other naval battle in history. Amongst the Allies, 36,200 sailors were killed and 175 allied warships and 741 RAF Coastal Command aircraft were lost.

Losses in merchant shipping were also high. Over 36,000 Allied merchant seamen lost their lives with 3,500 merchant ships sunk.

SS Athenia (of the British Donaldson Line), the first casualty of the Battle of the Atlantic

The Beginning

On that first day of the war when Neville Chamberlain broadcast to the British people about war with Germany, Admiral Karl Dönitz had already ensured that all his U-boats were at sea.

That evening the SS Athenia (of the British Donaldson Line) was heading for Montreal with 1,103 people on board having picked up passengers in Glasgow, Belfast and Liverpool. She was 60 nautical miles south of Rockall and 200 nautical miles northwest of Inishtrahull in Ireland when she was sighted by the German U-boat, U-30. At just after 7.30pm the U-boat fired two torpedoes. One hit the Athenia’s port side and exploded in her engine room. She immediately began to sink. Settling by the stern, she lost 117 civilian passengers and crew.

By this action, Dönitz had instantly shown his intent. His blockade of the UK with submarines would include merchant and civilian ships as well as warships.

This action was viewed as an outrage in Britain because Germany had immediately flouted the “Cruiser Rules” of the 1936 London Naval Treaty. This had been agreed by nations following Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare in the First World War. Essentially submarines were required to surface and place civilian crews and passengers in “a place of safety” (lifeboats did not generally qualify) before sinking a civilian ship. An exception was any ship that provided active resistance or refused to stop.

Britain immediately put in place a counter blockade of Germany which the Royal Navy started the following day and continued until the end of the war. However, the Royal Navy, like most, had not considered anti-submarine warfare as a tactical subject during the 1920s and 1930s especially after the London Naval Treaty. Consequently, at the beginning of the war, the Royal Navy was ill-prepared to fight a battle against the U-boats.

Admiral Karl Dönitz, German Commander-in-Chief of the U-Boats

Early Skirmishes (September 1939 – May 1940)

Initially, the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) was insufficiently strong to challenge the combined British and French Navies. Instead, Germany relied on commerce raiding using capital ships, armed merchant cruisers, submarines and aircraft.

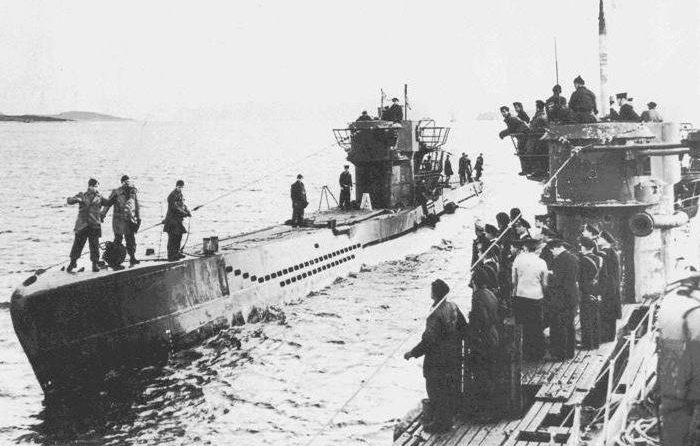

In readiness for the upcoming conflict, German warships were mostly at sea when war was declared. As well as the U-boats, the pocket battleships Deutschland and Admiral Graf Spee were already at large in the Atlantic. They immediately attacked British and French shipping. The U-boat fleet was small at the beginning of the war – about 57 boats – including the small and short-range Type II U-boats used primarily for mine-laying and for attacks in British coastal waters. This made up much of the early German anti-shipping activity in the early months of the war.

The Royal Navy quickly introduced a convoy system to protect and escort merchant shipping. This would be gradually extended out further and further from Britain, eventually reaching as far as Panama, Bombay and Singapore. Each convoy consisted of between 30 and 70 mostly unarmed merchant ships.

Winston Churchill, who at his point was the First Lord of the Admiralty, formed anti-submarine hunting groups based on aircraft carriers to search for German U-boats. This proved unsuccessful because U-boats were too elusive and British carrier-borne aircraft had inadequate weapons to attack the U-boats.

Within days Britain’s most modern carrier, HMS Ark Royal, narrowly avoided being sunk when three torpedoes from U-39 exploded prematurely. Another carrier, HMS Courageous, was sunk three days later by U-29 and less than a month later Günther Prien in U-47 penetrated the British base at Scapa Flow and sank the old battleship HMS Royal Oak at anchor.

Meanwhile in the South Atlantic, the Admiral Graf Spee had sunk nine merchant ships in the first three months of the war. British and French hunting groups that included battlecruisers, aircraft carriers and cruisers sought out the Deutschland in the North Atlantic and the Admiral Graf Spee in the South Atlantic. The latter was caught off the mouth of the River Plate between Argentina and Uruguay by a small British force. Suffering damage in a short action, the Admiral Graf Spee sought shelter in neutral Montevideo harbour before being scuttled by her crew on 17th December 1939.

After this initial burst of activity, the Atlantic campaign quieted down. The harsh winter of 1939–40 saw many of Germany’s Baltic ports frozen seriously hampering German offensive action. In the spring of 1940, the entire German fleet, including U-boats was required for the invasion of Denmark and Norway.

This campaign revealed serious flaws in the U-boats’ torpedoes. They were apt to explode inconsistently; either too early, too late or not at all due to a faulty firing mechanism. There were numerous opportunities for the U-boats to destroy British shipping, particularly at Narvik, but not one British warship was sunk by U-boats in more than 20 attacks during this campaign. These problems were resolved by early 1941 which resulted in the torpedo becoming a formidable weapon.

From the outset of the war, many Royal Navy ships were fitted with ASDIC (or SONAR as it was known in America). Its effectiveness was hampered by the use of the depth charge because this required an attacking vessel to pass over a submarine before dropping charges over the stern, resulting in a loss of ASDIC contact in the moments leading up to attack. The hunter was effectively firing blind, during which time a submarine commander could take evasive action. This problem was later cured with the introduction of the Hedgehog.

Type VII U-boat, the most commonly used U-Boat during the Battle of the Atlantic

The Happy Time (June 1940 – February 1941)

Despite the technical difficulties with their torpedoes, the period from June 1940 to early 1941 became known by the U-Boat crews as “The Happy Time”, a period during which Britain stood alone and was being stretched to its limit.

After the defeat of France, U-boats could operate from French bases giving them quicker and easier access into the Atlantic which they used with spectacularly success. This became the heyday of the famous U-boat aces like Günther Prien of U-47, Otto Kretschmer commander of U-99, Joachim Schepke of U-100, Engelbert Endrass of U-46, Victor Oehrn of U-37 and Heinrich Bleichrod, the commander of U-48. They became heroes in Germany as, between June and October 1940, over 270 Allied ships were sunk.

In August 1940, the Italians joined the Battle of the Atlantic. Twenty seven Italian submarines operated from the Betasom base in Bordeaux. Their submarines were designed to operate in a different way than U-boats. They had larger conning towers, a slow speed when surfaced and lacked the modern torpedo fire control making them ill-suited for convoy attacks. They performed better when searching for isolated merchantmen in more distant seas by taking advantage of their greater range and more comfortable living conditions. While their initial operations met with little success, their results improved over time and by August 1943, 32 Italian submarines had sunk 109 ships for the loss of 17 submarines, a return as good as the U-Boats. Additionally, the Italians were successful with their “human torpedo” chariots disabling several British ships in Gibraltar.

HMS Amethyst, a Flower Class Corvette. Typical of many that were built by Britain and Canada for Convoy Duty in the North Atlantic

Convoy Escorts (March – May 1941)

For the allies, the disastrous convoy battles of late 1940 forced the British to change tactics. They adopted permanent escort groups to improve the co-ordination and defence of merchant ships. They gradually increased the number of escort vessels available as old ex-American destroyers and the new British- and Canadian-built Flower Class corvettes came into service. There was a huge expansion in the Royal Canadian Navy, which grew from just a handful of destroyers to a fleet that could take an increasing share of the convoy escort duty. By this period American public opinion had begun to swing against Germany, but the battle was still essentially Britain and the Empire against Germany.

Initially, the new escort groups consisted of two or three destroyers and half a dozen corvettes. Since two or three of the group were usually in dock being repaired, the groups typically sailed with about six warships. The training of the escorts also improved as the realities of the battle became more clear. A new base was set up at Tobermory in the Hebrides to prepare the new escort ships and their crews for the demands of escort duty.

By March 1941, the Admiralty had moved the headquarters of Western Approaches Command from Plymouth to Liverpool with a secondary control bunker in Londonderry. This way they were much closer to the action and better able to control the Atlantic convoys. It also allowed for greater co-operation with supporting aircraft and, in April 1941, the Admiralty took over operational control of Coastal Command aircraft. New short-wave radar that could detect surfaced U-boats was fitted to both ships and planes.

Germany immediately felt the impact of the British changes. In early March, Prien in U-47 failed to return from a patrol. Two weeks later, in a battle with Convoy HX 112, the newly formed 3rd Escort Group of five destroyers and two corvettes held off a U-boat pack. U-100, detected by the new radar on the destroyer HMS Vanoc, was rammed and sunk. Shortly afterwards U-99 was also sunk and its crew captured. Dönitz had, in quick time, lost three of his leading aces: Kretschmer, Prien, and Schepke.

At this stage the convoys were not escorted for their complete journey across the Atlantic. The British covered the eastern side of the ocean and the Canadians the western. Convoys had to run the gauntlet in the middle. So Dönitz now ordered his wolf packs to operate further west in the middle of the Atlantic between these two areas in order to catch un-escorted ships. This new strategy was rewarded at the beginning of April when a wolf pack found Convoy SC 26 before its anti-submarine escort had joined. Ten ships were sunk, but another U-boat was lost.

The Enigma Machine, used by the German Military to send encoded messages

The U-boat operation generated extensive amounts of radio traffic between the U-boats and his headquarters. This, though, was via encrypted radio messages using the Enigma cipher machine which the Germans considered unbreakable. At Bletchley Park, British codebreakers desperately needed to understand the wiring of the German Naval Enigma rotors. The destruction of U-33 by HMS Gleaner the previous year had provided them with some information. But they had to wait until May 1941 for the breakthrough.

This came on the 9th May when crew members of the destroyer HMS Bulldog boarded the crippled U-110 and recovered all her cryptologic material, including bigram tables and current Enigma keys. This material instantly allowed all U-boat radio messages to be read for several weeks until the Germans changed the codes. However, there was now sufficient information for the codebreakers to be able to work out future codes.

In May 1941 the Germans mounted the most ambitious and serious raid on the convoys when the new battleship Bismarck and the cruiser Prinz Eugen put to sea with the specific aim of attacking convoys. A British fleet intercepted the raiders off Iceland where, in the Battle of the Denmark Strait, the battlecruiser HMS Hood was blown up and sunk. But Bismarck was also damaged and had to run to France for repairs. But before reaching her destination, she was disabled by an airstrike from the carrier HMS Ark Royal. The next day she was attacked and sunk by the Royal Navy’s Home Fleet. Her sinking marked the end of convoy raids by surface ships especially as the long-range search aircraft, the Catalina, now came into service and neutralised surface raiders.

The German Battleship Bismark

Growing American Involvement (June – December 1941)

In June 1941, the British decided that convoys needed to be escorted for the full length of the North Atlantic crossing. The Royal Canadian Navy on 23rd May established an escort force at St. John’s in Newfoundland that would operate in conjunction with the Western Approaches command in Liverpool. Six Canadian destroyers and 17 corvettes, reinforced by seven destroyers, three sloops, and five corvettes of the Royal Navy were assembled there. Their duty was to escort the convoys from Canadian ports to a meeting point south of Iceland, where the British escort groups would take over.

Increasingly the United States was being dragged into the war, despite its nominal neutrality. Large quantities of arms, ammunition and equipment were being manufactured in America before being moved to Canada for shipment to Great Britain.

In April 1941 President Roosevelt extended America’s maritime security zone as far east as Iceland, a country that Britain had occupied as soon as Germany had invaded Denmark in 1940. Roosevelt now agreed to provide garrison troops for Iceland in order to relieve British troops who were urgently needed elsewhere. As matters developed, America also started to escort Allied convoys from their ports to the meeting point south of Iceland resulting in a number of hostile encounters with U-Boats.

The Second Happy Time (January – June 1942)

For Germany, America’s entry into the War at the end of 1941 was going to alter everything. Dönitz decided to take the initiative and attacked shipping off the American East Coast. For this he needed the Type IX U-boats with the range to reach US waters. But he only could deploy a handful as the remainder had been diverted by Hitler to the Mediterranean to assist in protecting convoys supplying Rommel in the Desert. With just five U-boats, Dönitz planned to blockade American ports in Operation Drumbeat.

The USA was inexperience at modern naval warfare and sufficiently naive not to employ a black-out on its own shores. U-boats simply stood off shore at night and picked out ships silhouetted against city lights. This may have partly resulted from Admiral Ernest King, Commander-in-Chief of America’s Atlantic Fleet, dislike for the British. He rejected Royal Navy advice for a coastal black-out and for a convoy system. For his failure to implement this he received much criticism. Although no troop transport ships were ever lost in American coastal waters, merchant ships were left exposed and suffered as a result. Consequently, Britain hurriedly built coastal escort boats and provided them to the US in a “Reverse Lend Lease” deal.

Admiral Ernest King, American Commander-in-Chief Atlantic

The first U-boats reached US waters on 13th January 1942. By the 6th February they had sunk 156,939 tonnes of shipping without a single loss. To support the Type IX U-boats, Dönitz had by March also deployed Type VII U-boats. They were supported by Type XIVs that provided refuelling and replenishment at sea. By May they had sunk a further 397 ships totalling over 2 million tons.

That month Admiral King finally scraped together enough ships to establish a small convoy system. This quickly led to the loss of seven U-boats but they continued to operate freely throughout the Gulf of Mexico where they effectively closed several US ports. In July, Royal Navy escorts began to arrive in American waters and an interlocking convoy system for America’s Atlantic and Caribbean coasts was soon established. This resulted in an immediate drop in attacks in these areas and forced the U-boats to switch their attacks back to the Atlantic convoys.

The success of Dönitz’s Operation Drumbeat had demonstrated to Hitler how successful the U-boats could be in prosecuting an economic war on the Allies. Hitler thereafter gave Dönitz’s complete freedom to use U-boats for this purpose as he saw fit.

During early 1942, the U-boats switched to a new Enigma network called Triton that used a new, four-rotor, Enigma machine. Suddenly messages could not be read by Bletchley Park so the Allies no longer knew where the U-boat patrol lines were. This made it far more difficult to evade contact, and the wolf packs once again ravaged many convoys.

The Allies were forced to largely depend upon Huff-Duff. But in October crewmen from HMS Petard salvaged Enigma material from U-559 as she foundered off Port Said. This allowed Alan Turing at Bletchely Park to break the new Triton code. Now with knowledge of U-boat patrol positions, the allies’ shipping losses declined dramatically once more.

High-frequency direction-finding, or Huff-Duff as it was better known, was an invention of Robert Watson-Watt, the inventor of Radar. From 1942 onwards Huff-Duff was increasingly fitted to Convoy Escorts as an aid to locating U-boats.

Huff-Duff located the direction of a radio signal. Since the wolf packs relied upon U-boats reporting convoy positions by radio, there was a steady stream of messages to intercept. An escort ship could then sail in the direction of the signal and attack the U-boat, or at least force it to submerge causing it to lose contact thus preventing an attack on the convoy. Where two ships with Huff-Duff could both locate a transmission, the actual position, not just the direction, could be determined.

Sir Robert Watson-Watt, the British Inventor of Huff-Duff and Radar

The Battle of the Atlantic Returns to mid-Ocean (July 1942 – February 1943)

On 19th July 1942, Dönitz ordered the last U-Boats to withdraw from American coastal waters. Convoy SC 94 marked the return of U-boats attacks upon the convoys between Canada and Britain. At the same time Dönitz moved his U-Boat command to a newly constructed bunker at Château de Pignerolle just east of Angers on the River Loire.

He still had sufficient U-boats to spread across the Atlantic allowing several different wolf packs to attack numerous convoy routes. Often as many as 10 to 15 U-boats would attack in one or two waves. They would follow the convoys un-noticed by day and attacking at night. Convoy losses began to quickly increase again and in October 1942, 56 ships (totalling over 258,000 tonnes) were sunk in a gap in the air defence of convoys between Greenland and Iceland.

But U-boat losses also climbed. During the first six months of 1942, 21 U-boat’s had been lost while sinking over 800 Allied ships – this being less than one U-boat lost for every 40 merchant ships sunk. However in August and September, 60 U-Boats were sunk at a ratio of one for just 10 merchant ships destroyed.

Admiral Sir Max Horton. As Commander-in-Chief Western Approaches, he was responsible for convoy protection during the second half of he Battle of the Atlantic

On 19th November, Admiral Noble was replaced as Commander-in-Chief of Western Approaches by Admiral Sir Max Horton. With a growing number of escort ships available, Horton developed “support groups”, to reinforce convoys that came under attack. Unlike the regular escort groups, support groups were not directly responsible for the safety of any particular convoy. This gave them much greater tactical flexibility, allowing them to detach ships to hunt submarines spotted by reconnaissance planes or picked up by radar or Huff-Duff. Where regular escorts would have to stay with their convoy, the support group ships could break off and keep hunting a U-boat for many hours.

One tactic introduced by renowned escort commander, Captain John Walker was the “hold-down”. A group of ships would patrol over a submerged U-boat until it ran out of air and was forced to surface. This might take two or three days.

Following the Kriegsmarine’s defeat by the Royal Navy at Battle of the Barents Sea in December 1942, Hitler sacked Admiral Erich Raeder as its commander and appointed Dönitz’s in his place. In his new capacity as the Kriegsmarine’s Grand Admiral, Dönitz ensured that all ship building priorities would now be turned to U-boats.

By late 1942, Allied warships were being fitted with the Hedgehog, an anti-submarine spigot mortar which fired contact-fuzed bombs ahead of the firing ship while the target was still within that ship’s ASDIC beam. This was unlike depth charges which were launched behind and to the sides of the attacking ship and often resulted in ASDIC loss of contact. Hedgehog charges, which exploded on impact, allowed the attacking ship to change course and maintain contact as the target manoeuvred, as well as allowing for a normal depth charge attack. It solved one of the most pressing problems of keeping ASDIC contact at short ranges.

Captain John Walker (right) in action as the renowned and decorated Convoy Escort Commander in the Battle of the Atlantic

Climax of the Battle of the Atlantic (March 1943 – May 1943, “Black May”)

After winter weather provided a brief respite from the fighting, the spring saw convoy battles renew again with the same ferocity as before. The sheer quantity of U-boats in the North Atlantic now meant it was difficult for convoys to evade detection. Consequently, a succession of vicious battles took place.

In March 1943, the Germans added a refinement to the U-boat Enigma key, which blinded the Allied codebreakers at Bletchley Park for 9 days. That month in the North Atlantic, 82 merchant ships (totalling 476,000 tons) were sunk while 12 U-boats were destroyed.

The supply situation in Britain was becoming grim and supplies of fuel were particularly low. But then all of a sudden there was a complete reversal of fortunes.

In April, losses of U-boats increased while their kills fell significantly. Only 39 ships (totalling 235,000 tons) were sunk in the Atlantic while 15 U-boats were destroyed. By May, wolf packs no longer had the advantage with U-boat crews referring to the month as Black May.

The turning point had come in a battle centred on the slow convoy ONS 5 (April–May 1943). Made up of 43 merchant ships escorted by 16 warships, it was attacked by a pack of 30 U-boats. Although 13 merchant ships were lost, six U-boats were sunk by the escorts and by Allied aircraft. A storm then scattered the convoy but it managed to reach the protection of land-based air cover, causing Dönitz to call off the attack.

Two weeks later, Convoy SC 130 saw at least three U-boats destroyed and at least one U-boat damaged without any losses.

Worldwide, 43 U-boats were destroyed in that May, 34 of them in the Atlantic. This was 25% of Germany’s entire U-boat’s operational strength. The Allies lost 34 ships in the Atlantic during the month.

Facing a disastrous outcome, Dönitz called off operations in the North Atlantic, saying, “We have lost the Battle of the Atlantic”.

Depth charges exploding after being dropped by the British Destroyer HMS Vanoc

Final Years (June 1943 – May 1945)

During the last two years of the war Germany made several attempts to upgrade their existing U-boats while waiting for the next generation of U-boats, the Walter and Elektroboot types, to be built. Among the upgrades were improved anti-aircraft defences, radar detectors, better torpedoes, decoys, and snorkels which allowed U-boats to run underwater using their diesel engines.

Germany returned to the offensive in the North Atlantic in September 1943 with initial success attacking convoys. However a series of battles ensued resulting in less and less success for the U-boats. Over the next four months the allies lost eight ships (totalling 56,000 tons) plus six warships. But, critically, the Germans lost 39 U-boats, an unsustainable rate of loss.

Meanwhile the Luftwaffe introduced the long-range He 177 bomber and Henschel Hs 293 guided glider bomb. They claimed a number of victims but superior Allied air power prevented them from becoming a major threat.

None of the German technical improvements during this period were truly effective. By 1943 Allied air power was so strong that U-boats were being attacked in the Bay of Biscay as soon as they left port. The Germans had lost the technological race and so concentrated their efforts on lone-wolf attacks in British coastal waters while making preparations to disrupt the expected invasion of France.

Their losses continued with many U-boats sunk, usually with all hands. The allies were now making sure that they had won the battle to save being exposed to a U-boat threat on D-Day. Meanwhile supplies were pouring into Britain for the eventual liberation of Europe. Soon the U-boats would be critically hampered by the loss of their bases in France.

Late in the war, the Germans introduced the Type XXI U-boat and the short range Type XXIII. The Type XXI could run submerged at 17 knots which was faster than a Type VII at full speed surfaced. It was also faster than Allies’ corvettes. But by 1945, just five of these U-boats (and one Type XXI) were operational. It was all too little, too late for the U-boats.

As the Allied armies closed in on the U-boat bases in North Germany, over 200 boats were scuttled to avoid capture; those of most value attempted to flee to bases in Norway. In the first week of May, twenty-three boats were sunk in the Baltic while attempting to escape.

In one last fling, U-boats sank the steamer Black Point in American waters and on 7th and 8th May a Norwegian minesweeper and two freighters were torpedoed by U-boats in separate incidents. Finally, U-320 became the last U-boat to be sunk by an RAF Catalina; just hours before the German surrender.

The remaining U-boats, at sea or in port, were surrendered to the Allies, 174 in total. Most were destroyed by the Allies after the war.

The Saint Nazaire U-boat Pens built by the Nazis in France for easy access into the Atlantic

The Final Reckoning

The outcome of the Battle of the Atlantic was a strategic victory for the Allies on the basis that the German blockade of the UK failed. But this victory came at a great cost to both sides.

The Allies destroyed 783 German U-boats with over 30,000 U-boat sailors killed, the majority of which were in Type VII submarines. Of these, 520 were sunk by British and Canadian forces, while American forces accounted for a further 175 and 15 were destroyed by Soviet forces. 73 were scuttled by their own crews before the end of the war.

Additionally, Germany lost 47 other warships including 4 battleships (Scharnhorst, Bismarck, Gneisenau, and Tirpitz), 9 cruisers, 7 raiders, and 27 destroyers. Even Italy suffered; they lost 47 warships, 17 submarines and had over 500 sailors killed.

The Battle of the Atlantic involved thousands of ships in more than 100 convoy battles. Additionally there were an estimated 1,000 single-ship encounters in an area covering millions of square miles of ocean. The battle was very fluid and was constantly evolving as one side or the other gained an advantage through shifting alliances or through the advance of technology, weapons and tactics.

Overall the Allies gradually gained the upper hand. They largely overcome German surface raiders by the end of 1942 and had beaten the worst of the U-boat threat by the end of 1943.

The Battle of the Atlantic, with the exception of the Japanese invasion of the Alaskan Aleutian Islands, was the only battle of the Second World War that touched North American. U-boats disrupted coastal shipping and ports from the Caribbean to Halifax in Nova Scotia and even entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

At the end of the war, Rear Admiral Leonard Murray, the Canadian Commander-in-Chief in the North Atlantic, remarked, “The Battle of the Atlantic was not won by any Navy or Air Force, it was won by the courage, fortitude and determination of the British and Allied Merchant Navy.”

More Battles Fought by Britain during the Second World War:

WHEN BUYING FROM ANY REPUTABLE DEALER

Borrow any amount from £4,000 to £100,000